“Modernity is a qualitative, not a chronological category”

—Theodor Adorno

The following is a short extract from the first chapter in Hanzi Freinacht’s unpublished book ‘The 6 Hidden Patterns of History: A Metamodern Guide to World History’. The book is not coming out anytime soon, but a webinar on the topic of world history and the six metamemes will be held this autumn, four weekends in a row November 2–25. More details about the course can be found here.

Hanzi Freinacht: Let’s begin this chapter with a blurry “jpeg” image of the six metamemes, the six hidden patterns of world history.

Before we go on, I’d implore you to get a bucket and to keep it within reach. I expect especially postmodernly minded readers to react with strong contempt and violent allergy towards what follows. If this is you—if you find your fingers clutching spasmodically and a dark brooding voice inside you spells the word “linear”—just know your reaction is normal and an expected part of the process.

But do come back after you’re done vomiting—it gets more interesting, I promise. It’s a bit like Mother Ayahuasca, really: It takes a bit of throwing up to reach a breakthrough.

Here we go:

The Animistic metameme: Beginning with the “revolution of the upper Paleolithic” around 50 000 years ago. Characterized by animistic beliefs, totemism, shamanism, and ancestor cults that bind together larger bands of hunter-gatherers. This is also the metameme that gives rise to the first early art works.

The Faustian metameme: From the beginning of the agricultural revolution 12 000 years ago, blossoming with the great agrarian civilizations from around 4000 BCE. Characterized by notions of power gods, monumental architecture, and increased social stratification with privileged rulers on top with considerable means of organized violence. This is the metameme where we see the rise of powerful individuals.

The Postfaustian metameme: Beginning shortly before the axial age c. 800 BCE, in some aspects as early as 2000 BCE, but to its fullest extent only to blossom after 500 CE with the consolidation of the great moral religions such as Christianity, Islam and Buddhism. Characterized by transcendental ideas of salvation, literary traditions on ethics, and social critique. This is the metameme that gives rise to the so-called “righteous rebels”.

The Modern metameme: Beginning around 1500 CE, but in some aspects found in its proto-variant as early as 500 BCE. Blossoming only in the 19th and 20th century. Still the most prevailing metameme today. Characterized by rationalistic and scientific thought, notions of progress and material growth, and emancipation from arbitrary religious and political control.

The Postmodern metameme: Only to emerge in the 20th century, though some aspects appeared in the late 18th century. Yet to fully blossom. Characterized by a critique of rationalistic thought, established power relations and a greater concern with environmental and social issues.

The Metamodern metameme: Emerging as we speak.

Q: No, I’m fine. Really. Thank you for this introduction. Disgusting as it was.

…But it is linear—you really cannot deny that. I’m not saying this as a judgment, just a description. It’s a mainstream, Western, linear view of history. That has its place, perhaps, but it is of course not the only kind of history, nor necessarily the most relevant one in our day and age.

So your world history is for just seeing the basics from a Western mainstream perspective, as a linear progression, and then people can challenge it and nuance it, correct?

HF: No, it’s not linear, it’s not mainstream, and it’s not the Western standard (“Whig history”) model.

“Linear” means, by definition, that the more you add of something, the more of the same you get. Like following a line. Add more sugar, it gets sweeter. Add more salt, it gets saltier. Within certain ranges, these are linear equations.

Now, add more spirit worlds and rain dances… and you get high-rise pyramids, elaborate temple cities, and trade networks upholding armies allied with scribes who keep track of taxes and the number of captured slaves. To call that a linear equation is to take a very creative view on mathematics.

Add more of warrior god pantheon worship and bloody triumph of mass honor killings, and you get… Jesus. And the Buddha. And saints taking over from heroic warriors as the highest ideal of human accomplishment. And a universal order manifesting in literal wonders of beauty (cathedrals, mosques, and so on) that tower over every human settlement in honor of the divine, of universal brotherhood. Sure, linear.

And add some more of that, and you get… businessmen? Yes, lots of snazzy, shrewd capitalists turning everything under the sun into profit machines, with science itself serving as the strongest reinforcer for this to occur, until the entire world is swallowed up and ecosystems are destroyed. Some line we’re drawing. It’s a little curly, though, don’t you think? Like a spiral, even?

And add more of that, and you get… a whole blinking army of vegan feminists, intellectuals, and environmental activists who love diversity? And a virtual flood of obsessions with the minutiae of language use and its implications for social justice and power relations? Whoa. That would be postmodernism.

No, it’s not linear. The whole point of the model is that each stage is a qualitative shift, breaking the apparent “line” of the former metameme and taking a fundamentally different direction.

And it’s not the Western mainstream story, either. Because the Western mainstream would not admit that the postmodern minorities that emerge to critique it are absolutely right that the modern project is both tragic, doomed, and not a simple form of progress. And it would not admit that Animism was perhaps the best way for humans to live, nor that Postfaustian religions were in many ways a greater achievement than modern science, Modern Western mainstream historiography could even have problems admitting that colonialism was fundamentally a crime against humanity—and that global and big history must be released from the shackles of Western-centric parochialism, thereby honoring indigenous traditions as well as balancing the six, not one, mutually independent birthplaces of civilization: China, Indus River Valley, South America, Mesoamerica, Egypt, and Mesopotamia (where “Western civilization” is nothing more than a grandchild of the last two).

Postmodern historiography does see and admit these things. It does challenge the Western mainstream and its thinly disguised roots in 19th century colonialism, nationalism, and male-centrism. And my point is: Metamodern historiography entirely agrees, and seeks to proceed in this endeavor! We just want to do it better and more holistically, producing more useful theories for actually reducing the suffering of the world.

But the problem in our days, if you ask me, is that the postmodern mind cannot tell the difference between Modern historiography (yes, linear, Western, mainstream, apologetic for colonialism, blind to issues of gender and environment, reproductive of arbitrary power relations, and so on) and a Metamodern historiography, as the one in this book.

Understanding the metamemes, as the hidden patterns of history, is not the Modern mainstream history. It’s an expression of a Metamodern view of history, and as such it goes beyond Postmodern critiques of everything that moves (or everything that moves in what looks like a line).

Q: Nice. Sure, call me a postmodernist if that makes you feel safer in your Western-centric little ivory tower. I’m happy to be one if that means I fight against the long tradition of ranking peoples and cultures and epochs according to an unjust and cruel hierarchy of “evolution”. Folks like you are many, people like me are few and far between. The world needs a few of us as well.

And do tell me again that you have a more “evolved” perspective. It just proves my point: You are part of the same old, same old, white guy stuck in a square, wanting to box the world neatly into more rigid square boxes, to control it, and put yourself on top. Also in a box. I’d say it’s cute if I weren’t so utterly disgusted, given the profoundly murderous history of this very tendency. You’re even trying to appropriate the resistance of others and make it a part of your box-theory-of-boxing-everything-that-is-alive-and-organic-and-wobbly. You don’t like wobbly, I get it. You can’t handle it. It’s hard to control. I feel for you. It must be difficult to live so afraid of uncertainty, to be so much in need of controlling everything.

However, however. I do see what you mean about “linear”, I’ll give you that. That’s not exactly what I meant with linear, though. The fact still remains that you literally lined up the metamemes in a progression: I can flip back to the page, take a pencil, and draw a damned line between your stages or metamemes on the paper! But the sequence isn’t as simple as you say. You don’t claim that Animism grows out of Modernity, for instance. For my part, I can think of many ways in which it might, and it has—say, in the German Wandervogel or Lebensreform movements at the last turn of the century. People react against modernity and start seeing the spirits in nature, in their own people, reconnecting to the organic and simple, to the animal side of human life.

HF: Well, uhm. About me calling you a “pomo” (postmodernist)... Let me respond to that first and then get back to the main thread.

Please do note that you’re calling me an inheritor of positively genocidal tendencies and charging me with moral responsibility for those things. And then you’re calling me a box-man and all that, and going after my race and gender, framing me not for what I say but for external attributes I really cannot do anything about. At least you should ask yourself why you get to frame me and my argument but if I do the same to you, only in a less unfair manner (framing your position, not your skin color), I’m suddenly the pinnacle of evil? If you don’t like having your position framed as pomo, why then do you insist on framing my position, and also my person?

I guess I sometimes do call you “a pomo”, at least in regard to how vehemently you resist stage theories—or the good ones, not the poor ones. The difference is, though, that’s an assessment not of you as a person or collective category, but of the content of your argumentation. And not only that—it’s a fairly positive assessment. I thereby say that you hold almost all of the values that I also hold and cherish. It’s only that I have a different view on how to defend and manifest those values.

Q: Yada, yada. Hurt white men… Heroes of the whole world, who nobody in the world ever asked for. So sensitive. So fragile. Can’t take two seconds of critique. So used to being the talker.

HF: Sure. I don’t think we’re getting anywhere on that one. Back to the actual discussion, then.

I’m not saying that nothing Animist can ever come from modernity. I’m not. Indeed, this kind of emergence (earlier metamemes from later ones) is an important theme throughout this book. All of the metamemes always coexist as generative potentials.

What I am saying is that they must first emerge sequentially. There’s just no way for a band of twelve people in the desert foraging for roots to invent Newtonian physics and then to critique its implications on how it makes for a mechanistic cosmology and thus an alienating and anti-ecological worldview with a Cartesian ghost left echoing in the machine, feeling lonely. It just doesn’t happen. You don’t get Modernity and Postmodernity directly from Animism. You don’t. If that’s “too linear” for you, you’re just being dogmatic, sorry.

If I may deconstruct your position for a bit, you seem a bit stuck on the dogma, the underlying supposition, that lines are bad. But reality is more complex than that. Lines are sometimes good, sometimes bad. Lines do exist, also in living systems, even in mycelia. Sometimes lines describe the relationships between things accurately. The dance of the universe follows many geometric shapes, some of which happen to be lines.

Again, I said you’d really need a bucket, and I did promise you more interesting nuance if you could only finish vomiting. It’s normal. I understand. Just pull your hair back. Here’s some tissue.

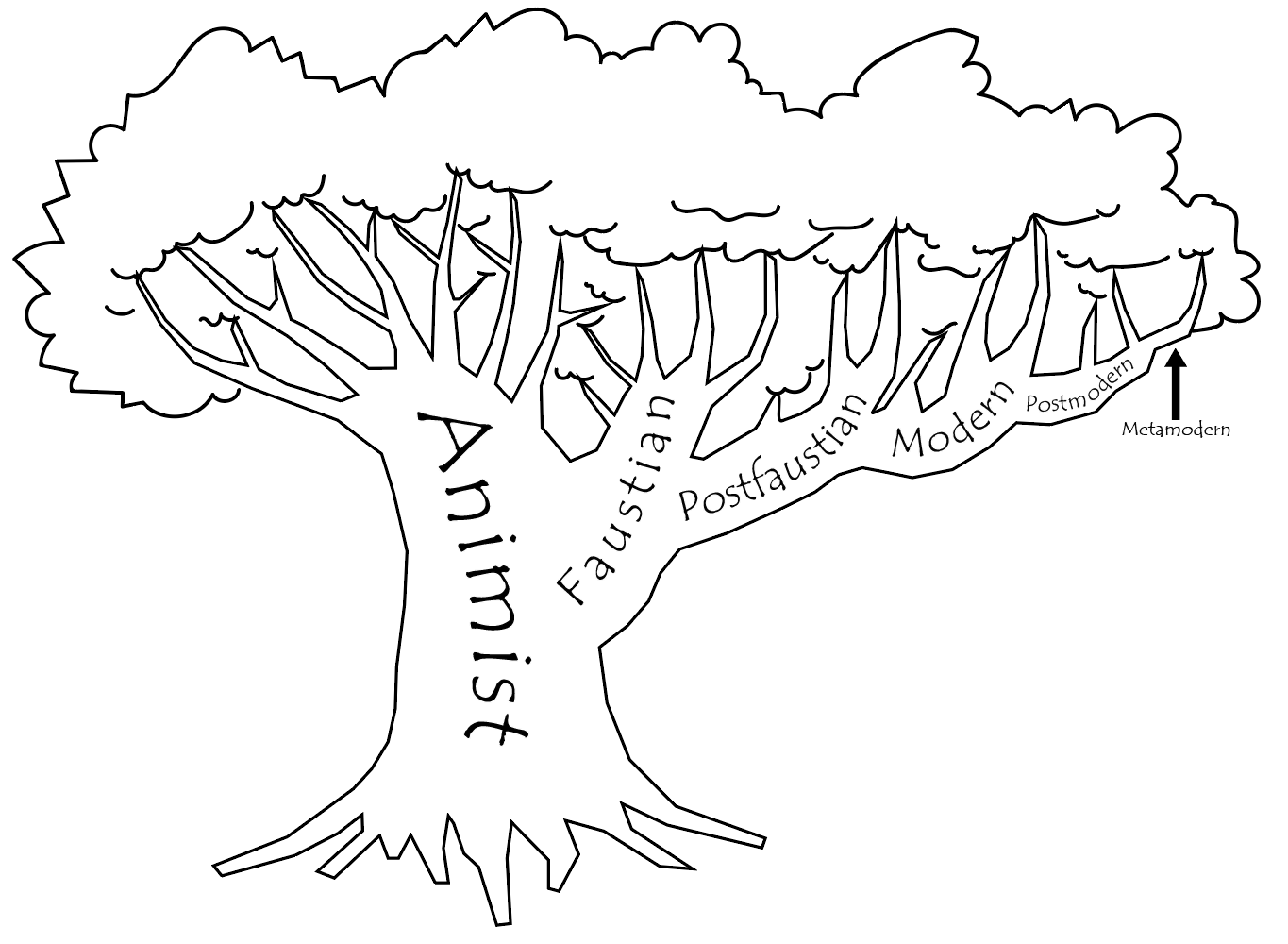

But just to really get the line-allergy issue under control, let’s do it like this. When I wrote the summary blurry jpeg image paragraph, I had little choice but to line the things up on the paper, indeed forming a line in a superficial sense. That’s a limitation of communicating in this format, on a two-dimensional surface, in text. A more accurate way of describing the progression of metamemes is that they branch off from one another in one tree, where each new branch is smaller and younger than the last. Like this:

I wish to credit my good friend Joe Lightfoot for being the one to come up with the idea of presenting the stages as a tree. For the rest of eternity, the official name for this model will thus be known as The Lightfoot Tree™.

The Lightfoot Tree™ illustrates the proportions of the stretches of time within which humans have lived in and expressed the different metamemes. In today’s world, modernity looks like the biggest one on the surface (because there’s just so much of it across the planet), but all of the oldest and in that sense most trial-and-error evolved cultures that jive with their direct environment are animist. Modernity is only about five centuries old. The oldest Animist cultures, say, the San people in the Kalahari desert, are literally close to a hundred times older. That’s the trunk of human experience. That’s the cultural and psychological homestead of humanity.

(And this model mirrors, by the way, the bifurcation diagram in chaos theory. It’s a bit more technical, and way ahead of where we are in the discussion, but I have added a discussion of the connection between metamemes and the bifurcation diagram in the appendix to this book. I recommend reading it, after having finished the book.)

Q: That’s… pretty gender-typical ‘splaining. But in keeping with my value of being a good listener (something white men with big ideas like yourself aren’t exactly known for), I’ll humor you. I know you’re trying to talk me into something, but hey, I’m confident I can resist so I may as well hear you out, even if I more or less already know what you’re going to say. Because I’ve already thought of this discussion and come farther than you have.

Okay, so let’s say you have these metamemes branching off organically from one another, where Animism is the biggest and oldest root, with tens of thousands of years of lived history. At least it’s better than a staircase of human history leading up to George H. W. Bush and the fall of the Berlin Wall. Modernity is just one of many ways that humans live and express themselves, fine. And Western societies are just one set of expressions, in turn, of modernity. There is so much human richness that arose long before anything one might call “modernity” ever appeared. And there do come beautiful and interesting things after and beyond it—sure, we can call that postmodern, if we want. A more critical and nuanced mind can notice that, for instance, an Amazon tribe’s shamanic practice can be wiser and more embodied than anything modern life ever cooked up in its soulless office landscapes.

But since you’ve added a stage after the Postmodern metameme, I can’t stop wondering if it wouldn’t be possible to add a stage before the Animistic one? (Again, I don’t buy the idea of stages, or branches or however you’d like sneakily to rebrand it, but I’ll play along to see how your thinking makes sense internally, regardless of my wider perspective. I’m just interested in the social phenomenon of people thinking like you do. I’ve always been like that, interested in people, even the bad ones and the vulnerabilities that drive them.)

HF: Ah, I’m happy we can speak on friendlier terms, even if just as a truce. It’s all I ask for. And yes, by the way, modernity is only one of many human expressions, and Western modernity is only a subcategory of that. Exactly correct, dear Q. And this whole “Western modernity” has been blown out of proportion in terms of its influence on the world, with partly disastrous consequences. We completely agree!

It’s just that to balance this out and bring about a global order that actually honors and integrates the multiplicity of human experience, we need to first admit that there is such a thing as modernity—the Modern metameme—and that it’s not the same as simply “being Western”. We need to understand what it actually is. And we need to not implicitly hold Western societies to a higher standard than other cultures, because that’s treating one thin sliver of human expression as the adult and all the others as the children. Western guilt vis-à-vis the rest of the world has an unfortunate way of smuggling Western supremacy in through the back door.

But, yes, whether there’s a stage before the Animistic one is a really good question. It’s almost as if I was telling you what to ask.

If it wasn’t for the fact that my publisher had already marketed this book as “The 6 Hidden Patterns”, we might as well change the title to “The 7 Hidden Patterns of History”. The Animistic metameme obviously didn’t appear out of nowhere, but emerged from a more rudimentary stage of development.

This more rudimentary stage doesn’t contain any of the Animistic metameme’s typical features such as spirit beliefs, mythological narratives, and works of art. I have refrained from dedicating a chapter to it since there really wouldn’t be much to say, and since most of it would be based on speculation anyway. The main way in which this—let’s call it the Archaic—metameme, differs from an “animal” condition to use a clumsy term, is in its technological features. It includes spoken language, domestication of fire, and tool use. These are the innovations that initially made humans, or more specifically hominids (since there were several subspecies of humans at this level of development), so different from other animals.

But, tellingly, the Archaic metameme left little to nothing in the way of art.

It had been around for over 300 000 years, maybe even more than a million (a group of archaeologists just unearthed the remains of what they believe is a one million years old campfire), since “the dawn of homo sapiens as a species”. It clearly encompassed other species of homo: homo habilis, homo erectus, Neanderthals, and Cro-Magnon. If we study the period of about 70 000 years ago, there were at least six different human species on earth.

It’s old. It’s Archaic. Hundreds of millennia of ongoing human life, and no art. That very fact should make us pause. It’s on the very edge between biological and cultural evolution, which is also why it encompasses different species of hominids.

Here’s the watershed moment where a cultural evolution began to decide the fate of biological evolution. That’s something we're entirely used to in the anthropocene, where mustard plants have become everything from spinach to cabbage to cauliflower, and wolves speciate into 360 species of dogs—biological realities that match cultural evolution (from herding to handbags and Hollywood showoff, in the case of shepherd dogs and chihuahuas). But 70 000 years ago, it was rare for culture to determine the fate of biological evolution—Archaic was shared across species of the genus “homo”, but when Animism took root, certain groups started to kick some serious butt and drove the others to a combination of extinction and biological assimilation. Culture had slowly started eating the biosphere already back then.

The Archaic metameme entails the beginnings of “culture” that accumulates learning in a way that makes culture come alive as its very own form of evolution. It is thus not only the first metameme, but also the first “hard” metameme. It established the foundational material conditions, or the “coordination engine” if we are to use my terminology, of the first human societies; a way of life that on a fundamental level remained the same until the agrarian age. But in between, with the emergence of animism, a new cultural superstructure was created on top of this hunter-gatherer coordination engine. But, in spite of all the cultural advances that animism brought about, the “hard” material conditions remained the same: people had to hunt and gather to get food, they depended on open fires for cooking and keeping warm, and they used language to coordinate life in small groups of wandering bands.

Q: Whoa, wait a second, “hard” metameme? “Coordination engine”? What do you mean? You can’t keep making up new words without explaining what you’re talking about.

HF: Oh sorry, I haven’t explained that yet. Take a deep breath and let me elaborate.

Q: You don’t need to tell me how to breathe, but go on.

If you wish to read the full chapter it can be accessed free of charge on the Metamoderna page here.

Best wishes,

Emil Ejner Friis

A webinar on the topic of world history and the six metamemes will be held this autumn, four weekends in a row November 2–25. More details about the course can be found here.

Hanzi Freinacht is a political philosopher, historian, and sociologist, author of ‘The Listening Society’, ‘Nordic Ideology’ and ’12 Commandments’. Much of his time is spent alone in the Swiss Alps. You can follow Hanzi on Facebook, Twitter, Medium and the Metamoderna website, and you can speed up the process of new metamodern content reaching the world by making a donation to Hanzi here.

For anyone looking to engage the full chapter, you can find it on the Metamoderna website, where there are lovely notes on coordination engines, purity generators, and more. Thanks Emil for sharing this here as well!